The Call of the Wild Active Reading Answers

Starting time edition cover | |

| Writer | Jack London |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Philip R. Goodwin and Charles Livingston Bull |

| Cover artist | Charles Edward Hooper |

| State | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Adventure fiction |

| Set in | Santa Clara Valley and the Yukon, c. 1896–99 |

| Publisher | Macmillan |

| Publication date | 1903 |

| Media blazon | Print (Serial, Hardcover & Paperback) |

| Pages | 232 (First edition) |

| OCLC | 28228581 |

| Dewey Decimal | 813.iv |

| LC Class | PS3523 .O46 |

| Followed by | White Fang |

| Text | The Telephone call of the Wild at Wikisource |

The Call of the Wild is a brusque adventure novel by Jack London, published in 1903 and set in Yukon, Canada, during the 1890s Klondike Gilded Blitz, when strong sled dogs were in high need. The central character of the novel is a canis familiaris named Buck. The story opens at a ranch in Santa Clara Valley, California, when Cadet is stolen from his home and sold into service as a sled domestic dog in Alaska. He becomes progressively more archaic and wild in the harsh surroundings, where he is forced to fight to survive and boss other dogs. Past the end, he sheds the veneer of civilization, and relies on primordial instinct and learned experience to emerge as a leader in the wild.

London spent almost a yr in the Yukon, and his observations grade much of the material for the volume. The story was serialized in The Sat Evening Mail service in the summertime of 1903 and was published later that year in volume form. The book's great popularity and success made a reputation for London. Every bit early as 1923, the story was adapted to film, and information technology has since seen several more cinematic adaptations.

Plot summary [edit]

The story opens in 1897 with Buck, a powerful 140-pound St. Bernard–Scotch Collie mix,[i] [two] happily living in California's Santa Clara Valley as the pampered pet of Judge Miller and his family. One nighttime, assistant gardener Manuel, needing money to pay off gambling debts, steals Cadet and sells him to a stranger. Buck is shipped to Seattle where he is confined in a crate, starved, and sick-treated. When released, Cadet attacks his handler, the "human in the red sweater", who teaches Buck the "law of order and fang", sufficiently cowing him. The human being shows some kindness after Buck demonstrates obedience.

Soon later, Buck is sold to 2 French-Canadian dispatchers from the Canadian government, François and Perrault, who have him to Alaska. Buck is trained as a sled dog for the Klondike region of Canada. In improver to Buck, François and Perrault add an additional 10 dogs to their team (Spitz, Dave, Dolly, Pike, Dub, Billie, Joe, Sol-leks, Teek, and Koona). Buck'southward teammates teach him how to survive cold winter nights and about pack society. Over the next several weeks on the trail, a bitter rivalry develops between Buck and the lead domestic dog, Spitz, a roughshod and quarrelsome white croaking. Buck somewhen kills Spitz in a fight and becomes the new pb dog.

When François and Perrault complete the round-trip of the Yukon Trail in record time, returning to Skagway with their dispatches, they are given new orders from the Canadian government. They sell their sled team to a "Scotch half-brood" human, who works in the mail service. The dogs must make long, tiring trips, carrying heavy loads to the mining areas. While running the trail, Cadet seems to have memories of a canine antecedent who has a brusque-legged "hairy homo" companion. Meanwhile, the weary animals become weak from the hard labor, and the wheel dog, Dave, a morose croaking, becomes terminally sick and is somewhen shot.

With the dogs likewise wearied and footsore to be of use, the mail-carrier sells them to three stampeders from the American Southland (the present-day contiguous United States)—a vain woman named Mercedes, her sheepish husband Charles, and her arrogant brother Hal. They lack survival skills for the Northern wilderness, struggle to control the sled, and ignore others' helpful advice—particularly warnings almost the unsafe spring melt. When told her sled is as well heavy, Mercedes dumps out crucial supplies in favor of fashion objects. She and Hal foolishly create a squad of xiv dogs, assertive they will travel faster. The dogs are overfed and overworked, and so are starved when food runs depression. Most of the dogs die on the trail, leaving but Buck and 4 other dogs when they pull into the White River.

The grouping meets John Thornton, an experienced outdoorsman, who notices the dogs' poor, weakened condition. The trio ignores Thornton's warnings about crossing the ice and printing onward. Exhausted, starving, and sensing danger ahead, Buck refuses to continue. Later Hal whips Buck mercilessly, a disgusted and angry Thornton hits him and cuts Cadet free. The group presses onward with the four remaining dogs, but their weight causes the ice to break and the dogs and humans (along with their sled) to autumn into the river and drown.

As Thornton nurses Cadet back to health, Cadet grows to beloved him. Buck kills a malicious man named Burton past tearing out his throat because Burton hit Thornton while the latter was defending an innocent "tenderfoot." This gives Buck a reputation all over the Due north. Buck besides saves Thornton when he falls into a river. After Thornton takes him on trips to pan for gold, a bonanza king (someone who struck information technology rich in the aureate fields) named Mr. Matthewson wagers Thornton on Cadet's forcefulness and devotion. Cadet pulls a sled with a half-ton (1,000-pound (450 kg)) load of flour, breaking it free from the frozen ground, dragging it 100 yards (91 m) and winning Thornton US$i,600 in gold dust. A "king of the Skookum Benches" offers a big sum (United states$700 at showtime, then $1,200) to buy Buck, but Thornton declines and tells him to go to hell.

Using his winnings, Thornton pays his debts but elects to continue searching for gold with partners Pete and Hans, sledding Buck and six other dogs to search for a fabulous Lost Cabin. Once they locate a suitable gilded find, the dogs find they accept zero to do. Buck has more ancestor-memories of beingness with the primitive "hairy man."[three] While Thornton and his two friends pan gold, Buck hears the telephone call of the wild, explores the wilderness, and socializes with a northwestern wolf from a local pack. However, Buck does not join the wolves and returns to Thornton. Buck repeatedly goes back and along between Thornton and the wild, unsure of where he belongs. Returning to the campsite i day, he finds Hans, Pete, and Thornton forth with their dogs have been murdered by Native American Yeehats. Enraged, Buck kills several Natives to avenge Thornton, then realizes he no longer has any human ties left. He goes looking for his wild brother and encounters a hostile wolf pack. He fights them and wins, then discovers that the alone wolf he had socialized with is a pack member. Cadet follows the pack into the forest and answers the call of the wild.

The legend of Buck spreads among other Native Americans as the "Ghost Dog" of the Northland (Alaska and northwestern Canada). Each yr, on the ceremony of his set on on the Yeehats, Buck returns to the former military camp where he was last with Thornton, Hans, and Pete, to mourn their deaths. Every winter, leading the wolf pack, Buck wreaks vengeance on the Yeehats "as he sings a song of the younger world, which is the song of the pack."

Main characters [edit]

Major dog characters:

- Buck, the novel's protagonist; a 140-pound St. Bernard–Scotch Collie mix who lived contentedly in California with Gauge Miller. However, he was stolen and sold to the Klondike by the gardener's assistant Manuel and was forced to piece of work as a sled domestic dog in the harsh Yukon. He somewhen finds a loving master named John Thornton and gradually grows feral as he adapts to the wilderness, eventually joining a wolf pack. Later Thornton'southward death, he is costless of humans forever and becomes a fable in the Klondike.

- Spitz, the novel'due south initial adversary and Buck's arch-rival; a white-haired husky from Spitsbergen who had accompanied a geological survey into the Canadian Barrens. He has a long career equally a sled dog leader, and sees Buck's uncharacteristic ability, for a Southland dog, to adapt and thrive in the Due north as a threat to his dominance. He repeatedly provokes fights with Buck, who bides his time.

- Dave, the 'wheel domestic dog' at the back stop of the domestic dog-team. He is brought North with Buck and Spitz and is a faithful sled domestic dog who only wants to exist left alone and led past an effective lead canis familiaris. During his second downwardly-trek on the Yukon Trail, he grows mortally weak, just the men accommodate his pride by allowing him to go along to drive the sled until he becomes and so weak that he is euthanized.

- Curly, a large Newfoundland dog who was murdered and eaten by native huskies.

- Billee, a expert-natured, appeasing husky who faithfully pulls the sled until beingness worked to death past Hal, Charles, and Mercedes.

- Dolly, a stiff croaking purchased in Dyea, Alaska by Francois and Perrault. Dolly is badly hurt after an assail of wild dogs, and she later goes rabid herself, furiously attacking the other sled dogs including Cadet, until her skull is smashed in by Francois equally he struggles to stop her madness.

- Joe, Billee'due south blood brother, merely with an opposite personality— sour and introspective. Spitz is unable to discipline him, simply Buck, afterwards rising to the head of the team, brings him into line.

- Sol-leks ('The Angry One'), a one-eyed husky who does not similar being approached from his blind side. Like Dave, he expects nothing, gives nothing, and only cares virtually being left alone and having an effective lead dog.

- Expressway, a clever malingerer and thief

- Dub, an awkward blunderer, always getting defenseless

- Teek and Koona, additional huskies on the Yukon Trail dog-team

- Skeet and Nig, two Southland dogs owned past John Thornton when he acquires Buck

- The Wild Brother, a alone wolf who befriends Cadet

Major human characters:

- Judge Miller, Cadet's first master who lived in Santa Clara Valley, California with his family. Unlike Thornton, he only expressed friendship with Buck, whereas Thornton expressed love.

- Manuel, Guess Miller's employee who sells Buck to the Klondike to pay off his gambling debts.

- The Man in the Cerise Sweater, a trainer who beats Buck to teach him the police force of the club.

- Perrault, a French-Canadian courier for the Canadian government who is Buck'southward offset Northland main.

- François, a French-Canadian mixed race homo and Perrault'southward partner, the musher who drives the sled dogs.

- Hal, an aggressive and trigger-happy musher who is Mercedes' blood brother and Charles' blood brother-in-law; he is inexperienced with handling sled dogs.

- Charles, Mercedes' husband, who is less violent than Hal.

- Mercedes, a spoiled and pampered adult female who is Hal'due south sis and Charles' wife.

- John Thornton, a gilded hunter who is Buck's final principal until he is killed by the Yeehats.

- Pete and Hans —John Thornton'due south ii partners equally he pans for golden in the E.

- The Yeehats, a tribe of Native Americans. After they kill John Thornton, Buck attacks them, and eternally 'dogs' them later going wild—assuring they never re-enter the valley where his terminal primary was murdered.

Background [edit]

California native Jack London had traveled effectually the United states as a hobo, returned to California to finish high schoolhouse (he dropped out at age 14), and spent a twelvemonth in college at Berkeley, when in 1897 he went to the Klondike by way of Alaska during the height of the Klondike Aureate Rush. Later, he said of the experience: "It was in the Klondike I found myself."[four]

He left California in July and traveled past boat to Dyea, Alaska, where he landed and went inland. To reach the gilded fields, he and his political party transported their gear over the Chilkoot Pass, oftentimes carrying loads as heavy as 100 pounds (45 kg) on their backs. They were successful in staking claims to eight gold mines along the Stewart River.[5]

London stayed in the Klondike for most a twelvemonth, living temporarily in the borderland town of Dawson Metropolis, before moving to a nearby wintertime camp, where he spent the wintertime in a temporary shelter reading books he had brought: Charles Darwin'southward On the Origin of Species and John Milton's Paradise Lost.[six] In the winter of 1898, Dawson Urban center was a city comprising almost 30,000 miners, a saloon, an opera business firm, and a street of brothels.[7]

Klondike routes map. The department connecting Dyea/Skagway with Dawson is referred to by London as the "Yukon Trail".

In the jump, as the annual aureate stampeders began to stream in, London left. He had contracted scurvy, common in the Arctic winters where fresh produce was unavailable. When his gums began to swell he decided to return to California. With his companions, he rafted two,000 miles (3,200 km) down the Yukon River, through portions of the wildest territory in the region, until they reached St. Michael. At that place, he hired himself out on a boat to earn return passage to San Francisco.[viii]

In Alaska, London found the fabric that inspired him to write The Phone call of the Wild.[4] Dyea Beach was the principal point of arrival for miners when London traveled through in that location, but because its access was treacherous Skagway presently became the new arrival point for prospectors.[ix] To reach the Klondike, miners had to navigate White Laissez passer, known as "Expressionless Equus caballus Pass", where equus caballus carcasses littered the route because they could not survive the harsh and steep ascent. Horses were replaced with dogs as pack animals to send material over the laissez passer;[10] specially stiff dogs with thick fur were "much desired, scarce and high in cost".[11]

London would have seen many dogs, especially prized husky sled dogs, in Dawson Metropolis and in the wintertime camps situated shut to the main sled route. He was friends with Marshall Latham Bond and his brother Louis Whitford Bond, the owners of a mixed St. Bernard-Scotch Collie dog near which London later wrote: "Yes, Buck is based on your canis familiaris at Dawson."[12] Beinecke Library at Yale Academy holds a photograph of Bail'due south dog, taken during London's stay in the Klondike in 1897. The depiction of the California ranch at the beginning of the story was based on the Bond family ranch.[xiii]

Publication history [edit]

On his return to California, London was unable to observe work and relied on odd jobs such as cutting grass. He submitted a query letter to the San Francisco Message proposing a story almost his Alaskan chance, only the idea was rejected because, as the editor told him, "Interest in Alaska has subsided in an astonishing degree."[8] A few years afterward, London wrote a short story about a dog named Bâtard who, at the terminate of the story, kills his main. London sold the piece to Cosmopolitan Magazine, which published it in the June 1902 outcome under the title "Diablo – A Dog".[fourteen] London's biographer, Earle Labor, says that London and then began piece of work on The Telephone call of the Wild to "redeem the species" from his nighttime characterization of dogs in "Bâtard". Expecting to write a short story, London explains: "I meant it to exist a companion to my other dog story 'Bâtard' ... simply it got away from me, and instead of iv,000 words it ran 32,000 before I could call a halt."[fifteen]

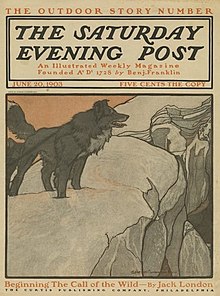

Written as a frontier story about the aureate rush, The Call of the Wild was meant for the pulp market. Information technology was showtime published in four installments in The Sabbatum Evening Post, which bought it for $750 in 1903.[sixteen] [17] In the same twelvemonth, London sold all rights to the story to Macmillan, which published it in book format.[17] The book has never been out of print since that time.[17]

Editions [edit]

- The beginning edition, by Macmillan, released in August 1903, had 10 tipped-in color plates by illustrators Philip R. Goodwin and Charles Livingston Bull, and a color frontispiece by Charles Edward Hooper; it sold for $1.50.[18] [nineteen] It is soon available with the original illustrations at the Internet Archive.[20]

Genre [edit]

Cadet proves himself as leader of the pack when he fights Spitz "to the death".

The Telephone call of the Wild falls into the categories of adventure fiction and what is sometimes referred to as the fauna story genre, in which an writer attempts to write an animal protagonist without resorting to anthropomorphism. At the time, London was criticized for attributing "unnatural" human thoughts and insights to a dog, and so much then that he was accused of existence a nature faker.[21] London himself dismissed these criticisms as "homocentric" and "amateur".[22] London further responded that he had ready out to portray nature more than accurately than his predecessors.

"I accept been guilty of writing two animate being stories—two books almost dogs. The writing of these two stories, on my part, was in truth a protestation against the 'humanizing' of animals, of which it seemed to me several 'animal writers' had been profoundly guilty. Time and again, and many times, in my narratives, I wrote, speaking of my canis familiaris-heroes: 'He did non remember these things; he merely did them,' etc. And I did this repeatedly, to the bottleneck of my narrative and in violation of my artistic canons; and I did it in order to hammer into the boilerplate human understanding that these domestic dog-heroes of mine were not directed by abstruse reasoning, but by instinct, sensation, and emotion, and past simple reasoning. Also, I endeavored to brand my stories in line with the facts of development; I hewed them to the marking set past scientific enquiry, and awoke, i day, to observe myself bundled neck and crop into the campsite of the nature-fakers."[23]

Along with his contemporaries Frank Norris and Theodore Dreiser, London was influenced by the naturalism of European writers such equally Émile Zola, in which themes such as heredity versus environment were explored. London's utilize of the genre gave it a new vibrancy, co-ordinate to scholar Richard Lehan.[24]

The story is also an example of American pastoralism—a prevailing theme in American literature—in which the mythic hero returns to nature. As with other characters of American literature, such every bit Rip van Winkle and Huckleberry Finn, Cadet symbolizes a reaction against industrialization and social convention with a return to nature. London presents the motif simply, conspicuously, and powerfully in the story, a motif later echoed past 20th century American writers William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway (most notably in "Big Ii-Hearted River").[25] E.L. Doctorow says of the story that it is "fervently American".[26]

The enduring appeal of the story, according to American literature scholar Donald Pizer, is that it is a combination of apologue, parable, and fable. The story incorporates elements of historic period-old brute fables, such as Aesop's Fables, in which animals speak truth, and traditional animal fables, in which the beast "substitutes wit for insight".[27] London was influenced by Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book, written a few years earlier, with its combination of parable and beast legend,[28] and past other creature stories popular in the early 20th century. In The Call of the Wild, London intensifies and adds layers of meaning that are lacking in these stories.[fifteen]

Every bit a writer, London tended to skimp on form, co-ordinate to biographer Labor, and neither The Call of the Wild nor White Fang "is a conventional novel".[29] The story follows the archetypal "myth of the hero"; Buck, who is the hero, takes a journey, is transformed, and achieves an apotheosis. The format of the story is divided into four distinct parts, according to Labor. In the outset office, Buck experiences violence and struggles for survival; in the second part, he proves himself a leader of the pack; the third part brings him to his death (symbolically and almost literally); and in the quaternary and last office, he undergoes rebirth.[30]

Themes [edit]

London'due south story is a tale of survival and a return to primitivism. Pizer writes that: "the potent, the shrewd, and the cunning shall prevail when ...life is unmerciful".[31]

Pizer also finds axiomatic in the story a Christian theme of love and redemption, as shown by Buck's refusal to revert to violence until after the death of Thornton, who had won Buck's honey and loyalty.[32] London, who went so far equally to fight for custody of 1 of his ain dogs, understood that loyalty betwixt dogs (particularly working dogs) and their masters is built on trust and dear.[33]

The Call of the Wild (cover of the June xx, 1903 Saturday Evening Post shown) is about the survival of the fittest.[26]

Writing in the "Introduction" to the Modern Library edition of The Telephone call of the Wild, East. L. Doctorow says the theme is based on Darwin'southward concept of survival of the fittest. London places Buck in conflict with humans, in conflict with the other dogs, and in conflict with his environment—all of which he must challenge, survive, and conquer.[26] Buck, a domesticated domestic dog, must call on his atavistic hereditary traits to survive; he must acquire to exist wild to go wild, according to Tina Gianquitto. He learns that in a earth where "the club and the fang" are police, where the police force of the pack rules and a good-natured dog such as Curly tin be torn to pieces by pack members, that survival by whatsoever ways is paramount.[34]

London also explores the idea of "nature vs. nurture". Buck, raised as a pet, is past heredity a wolf. The modify of surround brings up his innate characteristics and strengths to the indicate where he fights for survival and becomes leader of the pack. Pizer describes how the story reflects human nature in its prevailing theme of the force, particularly in the face of harsh circumstances.[32]

The veneer of culture is thin and fragile, writes Doctorow, and London exposes the brutality at the cadre of humanity and the ease with which humans revert to a state of primitivism.[26] His involvement in Marxism is evident in the sub-theme that humanity is motivated by materialism; and his interest in Nietzschean philosophy is shown by Buck's label.[26] Gianquitto writes that in Buck'southward label, London created a blazon of Nietschean Übermensch – in this case a dog that reaches mythic proportions.[35]

Doctorow sees the story every bit a extravaganza of a bildungsroman – in which a character learns and grows – in that Buck becomes progressively less civilized.[26] Gianquitto explains that Buck has evolved to the indicate that he is ready to join a wolf pack, which has a social structure uniquely adjusted to and successful in the harsh Chill environment, unlike humans, who are weak in the harsh surroundings.[36]

Writing mode [edit]

The first chapter opens with the outset quatrain of John Myers O'Hara'due south poem, Atavism,[37] published in 1902 in The Bookman. The stanza outlines one of the main motifs of The Call of the Wild: that Buck when removed from the "sun-kissed" Santa Clara Valley where he was raised, will revert to his wolf heritage with its innate instincts and characteristics.[38]

The themes are conveyed through London's use of symbolism and imagery which, according to Labor, vary in the different phases of the story. The imagery and symbolism in the first phase, to exercise with the journeying and cocky-discovery, depict physical violence, with potent images of pain and claret. In the second phase, fatigue becomes a dominant image and death is a dominant symbol, as Cadet comes close to existence killed. The third stage is a period of renewal and rebirth and takes identify in the spring, before catastrophe with the fourth phase, when Buck fully reverts to nature is placed in a vast and "weird atmosphere", a place of pure emptiness.[39]

The setting is allegorical. The southern lands represent the soft, materialistic world; the northern lands symbolize a earth across civilisation and are inherently competitive.[32] The harshness, brutality, and emptiness in Alaska reduce life to its essence, as London learned, and it shows in Buck's story. Cadet must defeat Spitz, the dog who symbolically tries to get ahead and take control. When Buck is sold to Charles, Hal, and Mercedes, he finds himself in a camp that is dirty. They treat their dogs badly; they are artificial interlopers in the pristine landscape. Conversely, Buck's next masters, John Thornton and his two companions, are described as "living close to the earth". They keep a clean camp, treat their animals well, and represent man'due south dignity in nature.[25] Unlike Buck, Thornton loses his fight with his beau species, and not until Thornton's death does Buck revert fully to the wild and his primordial state.[40]

The characters too are symbolic of types. Charles, Hal, and Mercedes symbolize vanity and ignorance, while Thornton and his companions represent loyalty, purity, and honey.[32] Much of the imagery is stark and uncomplicated, with an emphasis on images of cold, snow, ice, darkness, meat, and blood.[xl]

London varied his prose style to reflect the action. He wrote in an over-afflicted way in his descriptions of Charles, Hal, and Mercedes' camp as a reflection of their intrusion in the wilderness. Conversely, when describing Buck and his actions, London wrote in a fashion that was pared down and simple—a fashion that would influence and be the forebear of Hemingway'southward style.[25]

The story was written equally a frontier adventure and in such a way that information technology worked well equally a serial. As Doctorow points out, it is skilful episodic writing that embodies the style of magazine take a chance writing popular in that period. "It leaves us with satisfaction at its outcome, a story well and truly told," he said.[26]

Reception and legacy [edit]

The Call of the Wild was enormously popular from the moment it was published. H. 50. Mencken wrote of London'due south story: "No other popular writer of his time did any better writing than you lot will find in The Call of the Wild."[4] A reviewer for The New York Times wrote of it in 1903: "If goose egg else makes Mr. London'south book popular, information technology ought to be rendered then by the complete way in which information technology will satisfy the love of canis familiaris fights plain inherent in every man."[41] The reviewer for The Atlantic Monthly wrote that it was a book: "untouched by bookishness...The making and the accomplishment of such a hero [Buck] constitute, not a pretty story at all, merely a very powerful one."[42]

The book secured London a identify in the canon of American literature.[35] The first press of 10,000 copies sold out immediately; information technology is still i of the best known stories written by an American author, and continues to be read and taught in schools.[26] [43] It has been published in 47 languages.[44] London'due south first success, the book secured his prospects as a writer and gained him a readership that stayed with him throughout his career.[26] [35]

Afterwards the success of The Call of the Wild, London wrote to Macmillan in 1904 proposing a 2d book (White Fang) in which he wanted to describe the contrary of Buck: a dog that transforms from wild to tame: "I'm going to opposite the process...Instead of devolution of decivilization ... I'm going to give the evolution, the civilization of a domestic dog."[45]

Adaptations [edit]

The first adaptation of London's story was a silent film made in 1923.[46] The 1935 version starring Clark Gable and Loretta Immature expanded John Thornton'southward part and was the first "talkie" to characteristic the story. The 1972 movie The Telephone call of the Wild, starring Charlton Heston equally John Thornton, was filmed in Republic of finland.[47] The 1978 Snoopy Television special What a Nightmare, Charlie Brown! is another adaptation. In 1981, an anime film titled Telephone call of the Wild: Howl Cadet was released, starring Mike Reynolds and Bryan Cranston. A 1997 adaptation called The Phone call of the Wild: Canis familiaris of the Yukon starred Rutger Hauer and was narrated past Richard Dreyfuss. The Hollywood Reporter said that Graham Ludlow's adaptation was, "... a pleasant surprise. Much more faithful to Jack London'due south 1903 archetype than the 2 Hollywood versions."[48]

In 1983-1984 Hungarian comics artist Imre Sebök made a comic book accommodation of Call of the Wild, which was besides translated in German language. [49] A comic adaptation had been made in 1998 for Boys' Life mag. Out of cultural sensitivities, the Yeehat Native Americans are omitted, and John Thornton's killers are now white criminals who, as earlier, are also killed by Buck.

A television adaptation was released in 2000 on Fauna Planet. It ran for a single season of 13 episodes, and was released on DVD in 2010 as a feature film.

Chris Sanders directed another film adaptation titled The Telephone call of the Wild, a live-action/calculator-animated motion picture, released on Feb 21, 2020, past 20th Century Studios. Harrison Ford stars as the pb office and Terry Notary provides the movement-capture performance[50] for Buck the canis familiaris, with the canine character then brought to life by MPC'due south animators.

References [edit]

- ^ London 1998, p. 4.

- ^ London 1903, Chapter one.

- ^ London 1903, Affiliate 7.

- ^ a b c "Jack London" 1998, p. half-dozen.

- ^ Courbier-Tavenier, p. 240.

- ^ Courbier-Tavenier, p. 240–241.

- ^ Dyer, p. threescore.

- ^ a b Labor & Reesman, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Giantquitto, 'Endnotes', pp. 294–295.

- ^ Dyer, p. 59.

- ^ "Comments and Questions", p. 301.

- ^ Courbier-Tavenier, p. 242.

- ^ Doon.

- ^ Labor & Reesman, pp. 39–xl.

- ^ a b Labor & Reesman, p. 40.

- ^ Doctorow, p. xi.

- ^ a b c Dyer, p. 61.

- ^ Smith, p. 409.

- ^ Leypoldt, p. 201.

- ^ London, Jack (1903). The Call of the Wild. Illustrated by Philip R. Goodwin and Charles Livingston Bull (Beginning ed.). MacMillan.

- ^ Pizer, pp. 108–109.

- ^ "London Answers Roosevelt; Revives the Nature Faker Dispute – Calls President an Amateur"

- ^ Revolution and Other Essays: The Other Animals". The Jack London Online Collection. Retrieved April fifteen, 2010.

- ^ Lehan, p. 47.

- ^ a b c Benoit, p. 246–248.

- ^ a b c d e f thousand h i Doctorow, p. xv.

- ^ Pizer, p. 107.

- ^ Pizer, p. 108.

- ^ Labor & Reesman, p. 38.

- ^ Labor & Reesman, pp. 41–46.

- ^ Pizer, p. 110.

- ^ a b c d Pizer, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Giantquitto, 'Introduction', p. xxiv.

- ^ Giantquitto, 'Introduction', p. xvii.

- ^ a b c Giantquitto, 'Introduction', p. xiii.

- ^ Giantquitto, 'Introduction', pp. xx–xxi.

- ^ London 1998, p. 3.

- ^ Giantquitto, 'Endnotes', p. 293.

- ^ Labor & Reesman, pp. 41–45.

- ^ a b Doctorow, p. fourteen.

- ^ "Comments and Questions", p. 302.

- ^ "Comments and Questions", pp. 302–303.

- ^ Giantquitto, 'Introduction', p. xxii.

- ^ WorldCat.

- ^ Labor & Reesman, p. 46.

- ^ "Telephone call of the Wild, 1923". Silent Hollywood.com.

- ^ "Inspired", p. 298.

- ^ Hunter, David (1997-02-10). "The Phone call of the Wild". The Hollywood Reporter. p. 11.

- ^ "Imre Sebök".

- ^ Kenigsberg, Ben (xx February 2020). "'The Call of the Wild' Review: Human being's Best Friend? Drawing Dog". New York Times . Retrieved 24 August 2020.

Bibliography [edit]

- Benoit, Raymond (Summer 1968). "Jack London'due south 'The Call of the Wild'". American Quarterly. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 20 (ii): 246–248. doi:10.2307/2711035. JSTOR 2711035.

- Courbier-Tavenier, Jacqueline (1999). "The Call of the Wild and The Jungle: Jack London and Upton Sinclair'south Animal and Human Jungles". In Pizer, Donald (ed.). Cambridge Companion to American Realism and Naturalism: Howells to London. New York: Cambridge University Printing. ISBN978-0-521-43876-6.

- Doctorow, E. 50.; London, Jack (1998). "Introduction". The Telephone call of the Wild, White Fang & To Build a Fire. The Modern Library hundred best novels of the twentieth century. Vol. 88 (reprint ed.). Modern Library. ISBN978-0-375-75251-three. OCLC 38884558.

- Doon, Ellen. "Marshall Bond Papers". New Haven, Conn, Usa: Yale University. hdl:10079/fa/beinecke.bond.

- Dyer, Daniel (Apr 1988). "Answering the Call of the Wild". The English Journal. National Council of Teachers of English. 77 (four): 57–62. doi:10.2307/819308. JSTOR 819308.

- Barnes & Noble (2003). "'Jack London' – Biographical Note". The Call of the Wild and White Fang. Barnes and Noble Classics. Introduction past Tina Giantquitto (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble. ISBN978-1-59308-002-0.

- Barnes & Noble (2003). "'The World of Jack London'". The Phone call of the Wild and White Fang. Barnes and Noble Classics. Introduction by Tina Giantquitto (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble. ISBN978-1-59308-002-0.

- Giantquitto, Tina (2003). "'Introduction'". The Telephone call of the Wild and White Fang. Barnes and Noble Classics. Introduction past Tina Giantquitto (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble. ISBN978-1-59308-002-0.

- Giantquitto, Tina (2003). "'Endnotes'". The Telephone call of the Wild and White Fang. Barnes and Noble Classics. Introduction past Tina Giantquitto (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble. ISBN978-1-59308-002-0.

- Barnes & Noble (2003). "Inspired by 'The Call of the Wild' and 'White Fang'". The Call of the Wild and White Fang. Barnes and Noble Classics. Introduction by Tina Giantquitto (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble. ISBN978-1-59308-002-0.

- Barnes & Noble (2003). "'Comments and Questions'". The Telephone call of the Wild and White Fang. Barnes and Noble Classics. Introduction past Tina Giantquitto (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble. ISBN978-i-59308-002-0.

- Lehan, Richard (1999). "The European Background". In Pizer, Donald (ed.). Cambridge Companion to American Realism and Naturalism: Howells to London. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-43876-6.

- "Jack London's 'The Phone call of the Wild'". Publishers Weekly. F. Leypoldt. 64 (i). August 1, 1903. Retrieved Baronial 28, 2012.

- Labor, Earle; Reesman, Jeanne Campbell (1994). Jack London . Twayne's United States authors series. Vol. 230 (revised, illustrated ed.). New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN978-0-8057-4033-ii. OCLC 485895575.

- London, Jack (1903). . Wikisource.

- London, Jack (1998). The Call of the Wild, White Fang & To Build a Burn down. The Modernistic Library hundred best novels of the twentieth century. Vol. 88. Introduction past E. L. Doctorow (reprint ed.). Modern Library. ISBN978-0-375-75251-3. OCLC 38884558.

- Modernistic Library (1998). "'Jack London' – Biographical Annotation". The Phone call of the Wild, White Fang & To Build a Fire. The Modernistic Library hundred all-time novels of the twentieth century. Vol. 88. Introduction past E. L. Doctorow (reprint ed.). Modernistic Library. ISBN978-0-375-75251-3. OCLC 38884558.

- Pizer, Donald (1983). "Jack London: The Problem of Class". Studies in the Literary Imagination. 16 (ii): 107–115.

- Smith, Geoffrey D. (August 13, 1997). American Fiction, 1901–1925: A Bibliography . Cambridge University Press. p. 409. ISBN978-0-521-43469-0 . Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- "London, Jack 1876–1916". The telephone call of the wild. WorldCat. Retrieved Oct 26, 2012.

Further reading [edit]

- Fusco, Richard. "On Primitivism in The Call of the Wild. American Literary Realism, 1870–1910. Vol. xx, No. one (Fall, 1987), pp. 76–eighty

- McCrum, Robert. The 100 best novels: No 35 – The Call of the Wild by Jack London (1903) "The 100 all-time novels: No 35 – The Phone call of the Wild by Jack London (1903)".] The Guardian. 19 May 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

External links [edit]

- The Call of the Wild at Standard Ebooks

- The Call of the Wild at Projection Gutenberg

-

The Call of the Wild public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Call of the Wild public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Call_of_the_Wild

0 Response to "The Call of the Wild Active Reading Answers"

Post a Comment